My dual interest in alternate history has led me to speculate often on 'what might have been' if different actions had happened. And so, I present to you a brief speculation for your consideration.

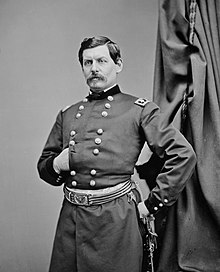

As history tells it, on November 7th 1862, George

B, McClellan, who had commanded the Army of Potomac for 16 months, was

dismissed by President Lincoln. In his 1864 The Army of the Potomac, General

McClellan's Report of its Operations While Under His Command McClellan relates that he was preparing to

deliver a great blow to Lee with his army in November. He had moved over

120,000 men in roughly two weeks towards Lee’s army in Virginia and by his own

accounts was preparing to force a battle upon Lee. In his Report he

relates that “I cannot doubt that the result would have been a brilliant

victory for our army.”[1]

Let us, for a moment, indulge

McClellan and assume that, for whatever reason, Lincoln decides not to dismiss

the general on November 5th, and instead allows him to continue in

his tenure as commander of the Army of the Potomac. What then, might have been

the result of McClellan’s cool belief in victory in 1864?

McClellan’s 1864 Report paints a far different picture

from his personal correspondence in 1862. He told his wife on the 25th

of October 1862 that he did not expect Lee to fight before Richmond[2]. He seemed

to set his own objective as Culpeper Court House, and from there we have no

clear idea of what he intended despite his later prediction of a great victory.

However, Longstreet beat McClellan

to Culpeper comfortably, moving in half the time it took him to

make the same march. Lee had nearly divined McClellan’s intentions by the 6th

of November[3]. He wrote that if the enemy continued to advance he would unite

Longstreet and Jackson’s corps through Swift Run Gap, joining at Madison

through Gordonsville. From there he anticipated the ability to menace

McClellan’s right flank. McClellan had fears regarding his army's ability to use the Orange and Alexandria RR and viewed its capacity as overrated[4], so he would most

likely then have directed his army to Fredericksburg. In his forward movement

however, he abandoned Ashby and Snicker’s Gap, this allowed Jackson to send men

across the Blue Ridge Mountains on the 13th and harass the armies’

rear columns historically.

Jackson suggested advancing his

corps to threaten McClellan’s flank and rear, which Lee agreed with should it

be feasible. Should the enemy further advance, Lee directed him to be pulled

back. In this instance, with McClellan’s slow advance still pushing forward,

but leaving his rear open. Jackson most likely mounts an embarrassing attack on

McClellan’s rear which gives him pause, and allows Jackson time to regroup with

Lee. However, if McClellan’s forward momentum continued positively on the 10th

and 11th, Lee might recall Jackson and continue to implement his

planned withdrawal to Madison. It should be noted that in his Report McClellan believed Jackson was at

Chester and Thorton’s Gaps, when in reality he was closer to Snickers and Ashby

Gaps[5], some 18 miles north, and so his rear is actually exposed rather than

covered. He had in fact, left his rear uncovered[6].

Delayed communications may allow

Jackson’s raid on McClellan’s supplies to go forward, but this will most likely

halt McClellan’s advance as he turns to meet this threat. Should Jackson

receive Lee’s orders to withdraw on the 13th as he did historically,

he would immediately make for the rendezvous with Lee. The timing of that can

only be speculated, but we should not assume he tarries long, and unites with

Lee at Madison.

In the face of a unified army,

and an increasing supply line. McClellan’s most likely option is to move his

force to Fredericksburg, which will make an advance of 35 miles. This movement

would take at best, four or five days, and at worst weeks. This would allow Lee

to discover the change of base, and either relocate himself for a defence on

the North Anna or to attack isolated portions of McClellan’s command. Most

likely, he does as he had done historically and moves to intercept McClellan at

Fredericksburg.

McClellan is now faced with a

prospect similar to that of Burnside in December of 1862. The question then is,

what does McClellan decide to do? Does he cross in the face of what he believes

to be superior numbers? Or does he sit and wait, planning a new campaign?

In the face of an entrenched enemy, it is likely the armies merely return to winter quarters. The upside may be that there is no disastrous Battle of Fredericksburg, as McClellan's dismissal and the obvious disposition of Lee's army make imminent action unlikely. From there though, it is anyone's guess as to how the campaign's play out in 1863. Does Burnside refuse the command and Hooker take over? None can say for sure.

In summation, I hope this lays out my reasoning behind my belief that even had McClellan been allowed to continue in his tenure of command, he would not have held it long. An extra month will not save him.

----

As a note, the letters referenced (unless otherwise specified) come from the War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War, Serial 28, available online through the Ohio State University.

[1] Report, pg. 652

[2] George McCllelan, The Young Napoleon, Stephen B. Sears, pg. 337

[3]Lee to Davis, Nov. 6th, 1862 (pg. 698): "General Jackson's corps is in the valley, his advance being at Front Royal. I do not think they will advance very far while he is in position to threaten their flank. Should they, however, continue their forward movement, General Jackson is directed to ascend the valley, and should they cross the Rappahannock, General Longstreet's corps will retire through Madison, where forage can be obtained, and the two corps unite through Swift Run Gap. No opposition has yet been offered to their advance, except the resistance of our cavalry and pickets. I have not yet been able to ascertain the strength of the enemy, but presume it is the whole of McClellan's army, as I learn that his whole force from Harper's Ferry, to Hagerstown has been withdrawn from Maryland, leaving only pickets at the fords, and but few troops at Harper's Ferry." See also, Lee to Stuart, Nov. 7th, 1862, pg. 703.

[4] George to Mary McClellan, Nov. 7th, 1862, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, pg. 520

[5] Report, pg. 652

[6] Report, pg. 651. See also, Lee to Stuart Nov. 9th, 1862, pg. 706-707