On this day, one-hundred and fifty years ago, the Red River Expedition reached Fort Garry. In what was one of the longest treks through wild country to assert national sovereignty, Garnet Wolseley led over 1,200 men to put down what was called the Red River Rebellion, but may more accurately be known as the Red River Resistance.

The catalyst for this incredible cross country trek was a series of poorly thought out land negotiations by the nascent Dominion of Canada. For decades men in what became Ontario had covetously eyed the vast, empty lands to the west Rupert's Land in what was controlled by the Hudson's Bay Company. Of course, these lands weren't really empty, but were home to many distinct and mostly thriving Indigenous cultures which had left their mark across the Great Plains for centuries.

One of these groups were the Métis. The Métis are a group of mixed ancestry, having been born from the union of various fur trappers with Indigenous women from across many tribes. They eventually formed their own distinct culture and community, many settling in the Red River Settlement, along the banks of the Red River between the Hudson's Bay trading posts of Upper and Lower Fort Garry. There they began to settle, mixing between sedentary farming and the great buffalo hunts which kept them fed when crops failed and harvests failed to materialize.

Along the banks of the Red River was also where the only sizable contingent of purely European settlers dwelled on the Plains north of the 49th Parallel. These were descendants of the colonists Lord Selkirk had brought in the 1810s to try and establish a more permanent presence on Hudson's Bay Company land. From there others, Americans, British subjects and French Catholics, traveled overland or the long arduous route from the sea to settle and farm. It was a mixing pot of peoples, multilingual and multicultural. Catholics and Protestants, Europeans, Métis and the Indigenous.

By the time Canada had obtained the Hundson's Bay Territory, the population was over 13,000, over half of them Métis. When the government had obtained the vast territory stretching from the Lake of the Woods to the Rockies, the people living in it were not consulted. They had no deed to their land and would be, under Canadian law, considered squatters. And so they were rightly terrified of this new development.

Anticipating the transfer, the government of Canada sent surveyors to Fort Garry in order to survey the land for settlement. The local representatives all said this was a poorly thought out idea which would cause unrest, but in typical form, the government went ahead and did it anyways. The surveyors, led by Colonel John Stoughton Dennis (one of the most singular cowards in Canadian history whose only previous claim to fame was bravely running away from the Battle of Fort Erie and having many high placed friends) was sent to command the surveyors. None of the surveyors spoke French, and they ignored all efforts by the locals to communicate. The local settlers, rightly irked by this development, coalesced around the son of a former prominent Métis leader, Louis Riel.

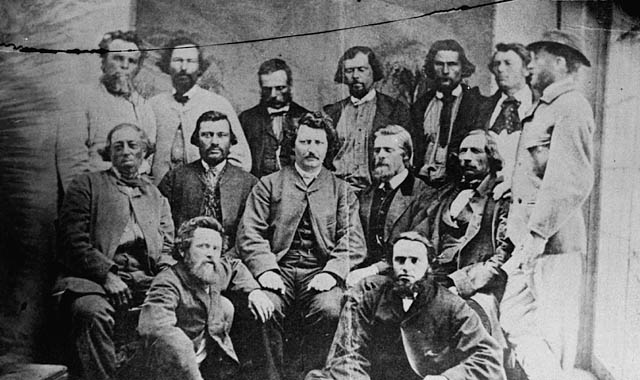

He swiftly formed a Provisional government, disrupted the survey work, turned back the governor sent by Canada and seized Fort Garry at the head of 400 men. In doing so he took effective control of the colony. The local Anglophones tried to rally around Colonel Dennis, but in the face of adversity he bravely dressed as an old Indigenous woman and ran away after other Anglophone leaders were arrested.

The Provisional Government then set about trying to negotiate a settlement with Canada. In doing so they established effective authority, managed to create Manitoba, and seemed to be on the path to effectively integrating into the new Dominion. However, the resistance of the Anglophone community was not yet done, and so some men continued to agitate. Though Riel had before pardoned men who had worked against him, he chose to make an example of one infamous trouble maker, Thomas Scott. Scott was an out and out racist who chose to quarrel with his guards and held the Métis in contempt. In order to demonstrate he was serious, Riel ordered his execution.

This set off a firestorm of condemnation in Ontario. The people were convinced that Riel meant to install a French Catholic government in the new Manitoba. They demonstrated, demanding vengeance for the death of Thomas Scott. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, who had until then been of the opinion that negotiation was the best option, could not let this go unanswered. He therefore ordered a military expedition be put together to assert Canadian sovereignty in the far flung province.

For this, the Canadian government selected the most capable officer of the Victorian Age to lead the expedition, Sir Garnet Wolseley. A man who had taken bullets for the Queen in Burma, Russia and India, he was practically bred for war. Acting as Quartermaster-General to the forces in Canada at the time, he was charged with raising a brigade of troops to serve on the expedition. He was assigned the 1st Battalion of the 60th Rifles under Lt. Col. R. J. Fielden (350 men and 23 Officers) and then two provisional battalions of militia from Ontario and Quebec, the Ontario Rifles under Lt. Col. Samuel P. Jarvis (382 men and 25 Officers) and the Quebec Rifles under Lt. Col. Louis Casault (385 men and 25 officers). Alongside these he had detachments form the Royal Artillery with four six pound guns, and men from the Royal Engineers, and voyageurs and guides. It was over 1,200 men.

Being his first independent command, Wolseley did much of the legwork for the planning himself. He consulted maps, other voyageurs, and many Canadians who had experience with the area. He also did all the calculations himself and tried to figure out how long exactly it would take them to reach their destination. He managed to calculate the number of supplies they would need down to the barrel, knowing they had to bring all of it with them themselves as there was no means of resupply along the route. Ammunition, food, clothing, axes and other implements would all have to go with them. Some of the tools sent by the Regular Army were considered shoddy, and so the Canadians themselves had to replace them with local made items. He recruited many useful officers from this Canadian experience, men he would rely on in later life, a Canadian, Frederick Denison who he would employ as chief of his voyageurs up the Nile trying to save Charles Gordon, Redvers Buller, who would serve as his chief of staff in many coming colonial campaigns, and William Butler whom he employed as a spy on the dangerous service of gathering information for him from Fort Garry before trekking to meet him in the wilderness.

It was a wild expedition, Fenians threatened to attack the column (they never did), the American government refused to allow the force use of the locks at the Sault Canal, and so they had to portage overland. It was a rough going, as they had to carry all they had with them past Thunder Bay along some slightly maintained roads. Christening his position Prince Arthur's Landing (though Wolseley felt it an 'ugly looking spot'), the men proceeded largely by canoe and portage. Though they were lashed at by rain, and kept up by thunderstorms, they persevered and moved on. They traversed from the new landing to Lake Shebandowan, overland again to Fort Frances and Lake of the Woods. The whole time they expected some form of attack, but their greatest enemies turned out to be the heat and the swarms of black flies and mosquitoes.

From there, after a brief misadventure where Wolseley's calculations and maps proved to be in error, they finally to the Winnipeg River and proceeded up to Lake Winnipeg, where they made camp and Wolseley mused on its picturesque appearance. After this, it was up the river to Fort Garry. They moved cautiously, expecting some form of resistance When Wolseley's brigade arrived, they found Riel had fled not long before their arrival as he had been (rightly as it turned out) told that the troops meant to hang him. Indeed, Wolseley's remarked "Personally I was glad Riel did not come out and surrender, as he at one time said he would, for I could not then have hanged him as I might have done had I taken him prisoner when in arms against his sovereign."

That being said, the expedition was a success. They successfully traversed through over 400 miles of wilderness to establish firm Canadian sovereignty over the new province of Manitoba. It was one of the largest military expeditions across the North American continent, and a feat of spectacular logistics through largely undeveloped wilderness. Not a single man got sick or was lost to disease or desertion. Despite the lack of fighting (as the whole 'rebellion' and expedition was a largely bloodless venture) it can safely be counted as one of the greatest feats of military movement of the 19th century, certainly the greatest of it's kind in Canadian history.

Much can be read about this, and Wolseley wrote extensively about it in his own memoirs The Story of a Soldier's Life (Volume 2). I would earnestly recommend reading the accounts of this adventure.

Wolseley would go on to earn laurels and undertake many successful campaigns in Africa and Asia. Riel on the other hand would flee into exile in the United States, only to return fifteen years later and lead an altogether more violent rebellion where he would be defeated, captured, and executed.

_poster.jpg)