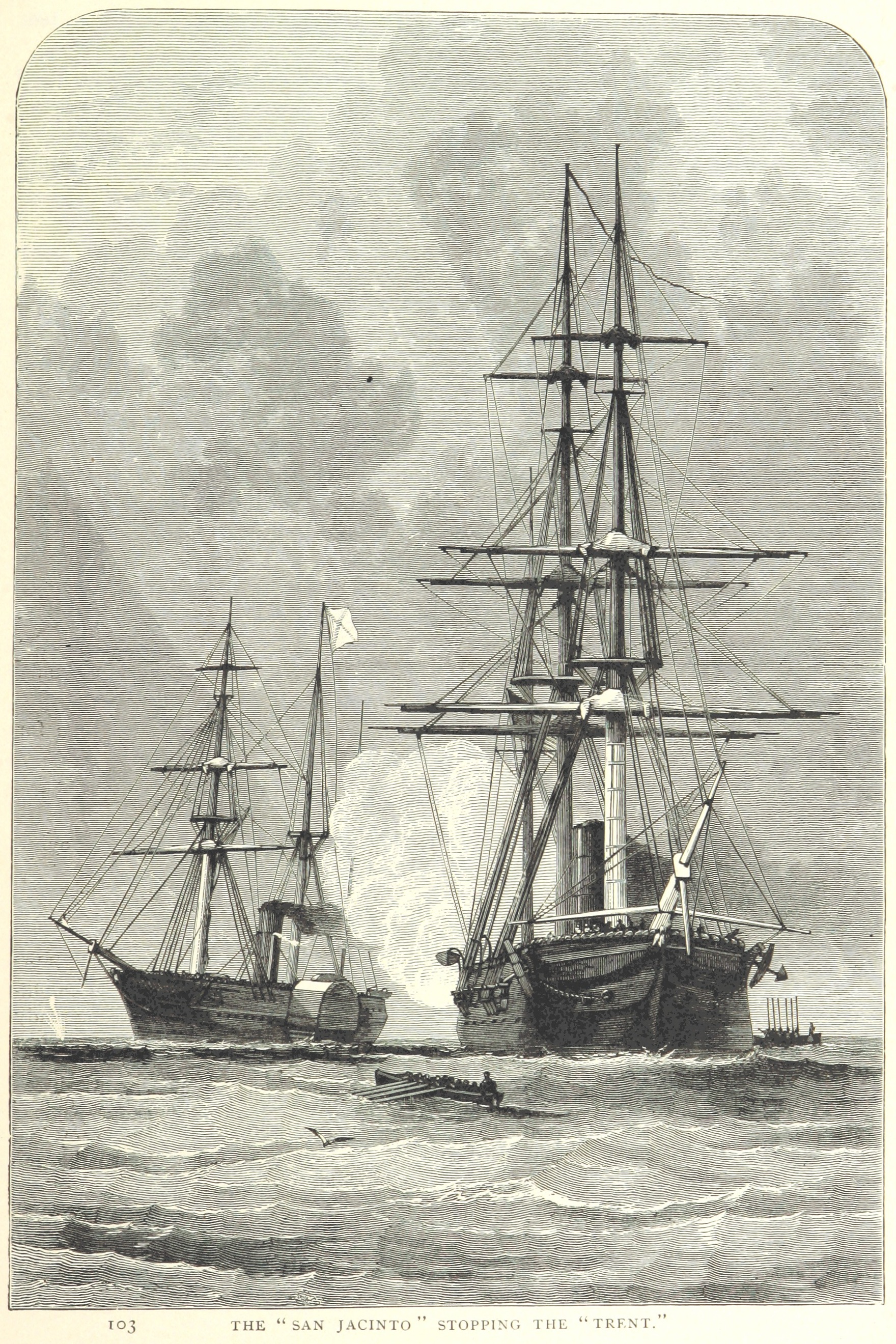

On this day, one hundred and sixty years ago, the United States warship, the USS San Jacinto, fired a warning shot across the bow of the British Royal Mail Steamer, the RMS Trent. In doing so, the captain of the Jacinto, commanded by Charles Wilkes, was taking an action which would nearly plunge the United States into war. Such a war would surely have been one of the greatest calamities of the 19th century, plunging the whole English speaking world into a conflict which would surely wrap the whole world in flames.

The Trent Affair, has been called the Cuban Missile Crisis of the 19th century, and coming almost exactly one-hundred years before that Earth shaking crisis, that is an apt comparison. For some background, the United States and the British Empire in 1860, were not good friends. While the US had close economic ties to Britain, and many immigrants from the British Isles (and primarily Ireland) still came to the US, the economic and political elite in Britain were somewhat aloof of "Cousin Jonathan" as the US was then known. There had been war scares since the War of 1812, with border crisis like the 1838 Caroline Affair, The Aroostook War, the Oregon Boundary Dispute, and only in 1859 the abortive "Pig War" which nearly set the two nations to war over a pig in the Pacific. In each case, cooler heads prevailed and diplomacy proved the order of the day.

In any case, in 1861 the slaves states in the Union seceded after the election of Abraham Lincoln to the White House. The new so-called Confederate States tried to form an explicitly slave holding republic, and in response the Union called for 75,000 volunteers to crush the rebellion. From there, four years of bloodletting followed. That same year, Britain declared neutrality in the conflict, granting belligerent rights to both sides. This outraged the Union as they felt it was a step towards recognizing the Confederacy as an independent nation, as it granted some recognition of Confederate warships, and the right to take on provisions. Though this was not, in fact, a step towards recognition, it did show a certain bias in British thinking at the time. They remembered how the Thirteen Colonies had been impossible to subdue, and many concluded that the Confederacy - with roughly as much territory as western Europe - in seceding was a fait accompli which would mean it was only a matter of time before the North was forced to recognize that the United States were united no more.

Of course, the Union would not do that without a fight, and so the Confederates sought proper recognition from the powers of Europe. This was exactly why the Jacinto stopped the Trent, in order to seize two Confederate diplomats bound for Britain and France. Truthfully, the account of this stop and seizure must be read to be believed, from belligerent passengers facing down armed US Marines, diplomats hopping through portholes, and a swell on the waves nearly knocking everyone together in a dangerous pile of bayonets and human limbs, it is a minor miracle that no one was hurt, let alone killed. And historically, even with British outrage, the Trent Affair was resolved diplomatically.

This of course begs the question, well what would have happened if someone had been killed and the crisis was not resolved diplomatically? The answer is war, a great and terrible war.

For simplicity, we can assume that someone is killed on board the Trent and Britain is outraged. Abraham Lincoln of course would not be fool enough to intentionally goad Britain into war, and most likely he would have either capitulated, or pushed for foreign mediation of the problem. Ironically, he would have run into what in the 21st Century we would term, a public relations problem. As mentioned, many in Britain assumed that the secession of the South was a done deal, and the North would have to cut its losses. The other thing many assumed was that in doing so, the United States would make good on those losses and turn around and invade Britain's North American possessions in Canada to do that. This was not helped that those making decisions in London did not know much about Lincoln and his cabinet, it had only one recognizable man, William Seward. The problem was that William Seward was known for often saying the US should invade and annex Canada, which naturally - to the British Prime Minister at the time, Lord Palmerston - meant that this was indeed the plan.

Historically, when the British responded to the Trent Affair, they sent an ultimatum with an expiration date of seven days. This was to ensure that the United States could not do what many in Britain feared it would do and simply make peace with the South, turn its armies north, and seize Canada. If Lincoln were, in this counterfactual scenario, to send a suggestion hoping for international arbitration, Britain would most likely see this as a stalling tactic and prepare for war.

Truthfully, that is exactly what took place historically. Britain, upon receiving news of the events on the Trent, ordered out 11,000 soldiers and all the arms and other engines of war they would need. At the same time, in the United Province of Canada, orders were given in late December to muster 38,000 militia, while in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, new volunteer companies were being formed. The British were evidently prepared to send 28,000 men immediately to North America. How many Canadians could have been mustered and armed is an open question, but in April of 1862, 14,000 men were available, and it is hard to doubt that in a war crisis, anything less could have been raised, and more surely could have. Should the British have fully committed to the war they could have mustered a great number of soldiers from the British Isles, troops stationed in the Mediterranean, and other places. The crisis did end historically in December, but had more men been sent, the size of the British forces prepared to fight the Americans would not be inconsequential.

The United States army in early 1862 numbered over 500,000 men. Nothing to sneeze at! However you can't move all those men to attack Canada, you need many facing off against the Confederacy, will have to dislodge others to defend the coasts, and some are also serving in the interior or in California! My own guess is the Union could shake loose roughly 12-14 divisions (3 Corps) to defend New England and invade Canada, call that roughly 150,000 men overall.

On the naval side, there is more of a mismatch. In 1862, the size of the Royal Navy showed over 465 screw vessels, 115 paddle vessels and 110 sailing ships, totaling 690 vessels in all. I provide here another tabulation here which shows only the major sailing ships and not the nearly 200 gunboats in service, which can be perused in the December 1861 Naval List. It should however, be a sobering number in comparison, with roughly 339 active ships worldwide.

The United States Navy, by contrast, had 264 ships. Of these however, roughly only 100 vessels were steamships, the remainder being sailing ships or other ships converted for the needs of the naval blockade. Not many are fast or modern steamers, or even proper warships. This puts them at a severe disadvantage.

Important to note however, that at the start of the war Britain has an advantage in ironclads. Whether it be older broadside batteries built for the Crimean War, or modern warships like the ironclad HMS Warrior or her smaller sister Defence, the British can send larger and superior ships to North American waters. The USS Monitor would not be launched until March, and she is restricted to New York, and her only company would be the USS Galena, who had very thin armor compared to any other ironclad of the period. Sister Monitors would most likely only be rolling out roughly 90 days after the Monitor's initial launch. This leaves very little to hold the line until roughly June/July 1862, and the British too will be building more ironclads of their own.

Not only will this war not be confined to the Atlantic, but on the Great Lakes both sides will be scrambling flotillas of gunboats. On Lake Erie, the US has an advantage by having the only functional warship, the USS Michigan, but on Lake Ontario, they will be scrambling to catch up as Britain can send gunboats or ironclads up the Saint Lawrence to help control that lake and defend Canada. The Richelieu River would also end up as a battleground as well, with flotillas needed to be constructed to defend or attack towards Montreal. In each case the Canadians have an initial advantage due to the proximity of British guns and sailors and access to the St. Lawrence once it opens in the spring.

We do of course need to discuss the third combatant, the Confederacy. They would have roughly 270,000 troops present for duty at the start of 1862, and without the need to defend their own coasts from attack, would be free to redeploy thousands to support their armies in Virginia and Tennessee. Though they don't have much of a navy, that doesn't really matter when you have the biggest navy on Earth stepping up for you does it?

This is, very roughly, the strength of the various sides going to war in 1862 should this war go hot.

How then, might this war be carried out?

At some point in early January/February 1862 the USN and Royal Navy will fight a series of skirmishes, ranging from ship to ship fights to more than likely one pitched battle in the North Atlantic and the Caribbean. We know roughly what the British hoped thanks to a brilliant article by Kenneth Bourne, commissioners appointed to the task in 1862, and the British commander of the North American and West Indies Squadron did leave ideas for what he hoped to accomplish written down. This would mean that in the first months of the war Britain would be putting most of her efforts into either destroying or driving to port as much of the USN as they could. This would maybe net a few modern ships, but I credit the US enough to think they would begin evacuating ships and men from likely points of attack by the RN once the British minister in Washington leaves, while leaving just enough old or less reliable ships (and men in forts) to hold what they have and enforce a legal blockade so that in the event war does not break out, they cannot be said to have let up on the blockade.

These first few months would lead to a depressing bit reading in the North as the newspapers reported on forts captured, ships sunk or captured, and likely thousands going to prison camps in British colonies or the Confederacy. Many ships though, would make it to port, and be able to harass the British as they tried to set up a blockade of over 1,200 miles of coastline. There is no serious doubt they could sustain this blockade, merely how long it may take to be effective.

While Britannia rules the waves, much of the war on land would be stalled. The British would have advanced partially overland, seizing posts across the border in Maine to control the route their soldiers historically marched through. They may also launch an overland raid into New York to seize (or more likely raze) the incomplete Fort Montgomery at the head of Lake Champlain. This would undoubtedly cause outrage in the Union, and they would be chafing for the chance to strike back.

We can also make a pretty good guess on how this would go as none other than future General in Chief of the Union armies Henry Halleck had written about the most important way to attack Canada in the 1840s, an overland attack on Montreal. This serves two purposes, first it cuts off the western portion of Canada (modern Ontario) from support from Britain by sea, and secondly it delivers control of the Saint Lawrence River below Quebec to the invader. Most likely an army would (as had been done in 1775 and 1812-13) advance up the Richelieu River to attack the city and attempt to take it.

Problematically, the British know this, and would most likely be prepared to meet the Union somewhere on the field of battle in between. Expect the first great clash between an American "Army of the Hudson" and the British "Army of Canada" somewhere along the banks of the Richelieu in May of 1862.

Meanwhile the Union would be sending an army to invade Canada West. This would both tie down troops otherwise intended to defend Montreal, and also snag bits of British territory to use as bargaining chips at the peace table. If they could cross the Saint Lawrence and take Kingston, they would be able to concentrate on besieging Montreal and then potentially Quebec.

The British for their part, wished to attack the city of Portland Maine in order to seize an all weather railroad terminus at the Atlantic. This would most likely lead to a British attack, and potentially siege, of the city, further tying down US troops who would otherwise be used elsewhere.

What then is the Confederacy doing? Considering they could have gathered as many as thirteen divisions in northern Virginia (potentially 125,000 men) I think that Joseph Johnston would be under great pressure to attack Washington. Meanwhile, McClellan and the Army of the Potomac (most likely a similar size) is going to be waiting to either attack or be attacked. How that campaign would play out would be up in the air, but it would feature two of the largest armies ever assembled in North America going head to head. Considering the fair amount of blunders and problems in handling command and control in 1862 on both sides in the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles, I don't expect anything definitive to be decided.

Out West, a similar situation holds true. Albert Sydney Johnston (historically of Shiloh fame) would most likely find himself facing a similar situation he faced in April of 1862 historically, but now he has access to everything he can get his hands on. I fully anticipate he may go forward and attack the still disparate Union armies and re-invade Kentucky. Will he prove more successful than Braxton Bragg?

Beyond the Mississippi, I can see little really changing, though some quirks of fate may drive the Confederate fortunes better or worse. On the Pacific slope, other than a blockade of San Francisco, the British probably seize the San Juan Islands, bloodlessly ending the Pig War.

My own expectation is that by July of 1862, the British will have seized Portland, while blunting the early invasion of Canada East, keeping them out of Montreal. In Canada West, the Union will have captured Toronto and everything west of it. Meanwhile, on the Virginia front, two massive armies will grapple with one another like clumsy giants, pushing the battle lines north or south as the fortune of war goes, though to give credit I do think McClellan could push the Confederates out of Centreville and towards the Rappahannock. Out west, the Confederates, if they do better than at Shiloh historically, blunt any invasion and are marching back up the river towards Nashville, seeking to drive the Union out.

Where the war goes from here, who can say? Economically, the Union would be in a pickle as the blockade would hurt their economy, and most Union finances came from either money earned on the tariff, taxes and printing money. The Confederate economy relied on printing money and it sent them into an economic tailspin that ended up destroying the nascent nation as effectively as Union cannon and warships. The blockade would hurt, while perversely the Confederacy is open for business and can sell cotton on the world market to their hearts content, which most likely makes for a much better economic situation. Britain too would be hurt, but not nearly so badly as the United States.

If Lincoln can politically manage to accept a 'white peace' with mild reparations before the end of 1862, he absolutely will. However, should he be unable to do so, I can unfortunately see the war dragging into 1863-64 to the Union's detriment. Every year another man, rifle and bullet is spent fighting Britain in Maine or Canada, is another year the Union is not fighting the Confederacy and not strangling their economy. Even should the Union make peace with Britain, is it likely they can turn around and continue the war into 1865, or potentially even 1866? This is perhaps the only scenario where the Confederacy could emerge as a functional and not economically wrecked nation, and if it did, that would have terrible consequences for world history as the Slave Power pushes on.

I do not regard this as a good outcome. North America would be divided between four nations (Canada, The US, CSA and whatever happens in Mexico) all of whom may have reason to distrust one another. Canadians would feel bound to the mother country more than ever, and the Confederacy, if it gained its independence by foreign assistance, would most likely seek out foreign allies.

I've covered the bare bones here, but there's much more to talk about. I've explored the topic myself, and am currently writing a projected trilogy which would cover just such a war. The first book Wrapped in Flames, is currently closing in on the 50% finished mark. I'd love to hear other thoughts on the idea, and it is one which is extremely intriguing and still worth exploring.

.jpg)